-- Environment

|

* Home

* History * Population * Government * Politics * Lobbyists * Taxes * State Symbols * Biographies * Economy * Employers * Real Estate * Education * Recreation * Restaurants * Hotels * Health * Environment * Stadiums/Teams * Theaters * Historic Villages * Historic homes * Battlefields/Military * Lighthouses * Art Museums * History Museums * Wildlife * Climate * Zoos/Aquariums * Beaches * National Parks * State Parks * Amusement Parks * Waterparks * Swimming holes * Arboretums More... * Gallery of images and videos * Fast Facts on key topics * Timeline of dates and events * Anthology of quotes, comments and jokes * Links to other resources |

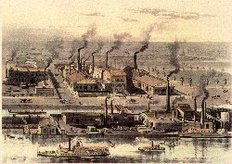

The Balbach Smelting & Refining Company on the Passaic River in the Ironbound section of Newark was the second largest metal processing enterprise in the United States from the late 19th century to its closure in the 1920s. The plant's site was subsequently redeveloped as the current location of the baseball fields of Essex County's Riverbank Park. Image: Wikimedia Commons/Newark Public Library The Balbach Smelting & Refining Company on the Passaic River in the Ironbound section of Newark was the second largest metal processing enterprise in the United States from the late 19th century to its closure in the 1920s. The plant's site was subsequently redeveloped as the current location of the baseball fields of Essex County's Riverbank Park. Image: Wikimedia Commons/Newark Public Library

- Overview

For most of its history, New Jersey public policy largely ignored practices which would later be found to have severe adverse impacts on its environment. The state's encouragement of industrial development in the nineteenth century led to widespread air and water pollution, along with the disposal of solid and hazardous waste at dumps throughout the state. Apart from industry, the state and local governments took no responsibility for the treatment of human waste, uniformly discharging raw sewage into rivers and the ocean.  Illegal dump along New Jersey Turnpike in photo taken circa 1970s. Image: Wikimedia Commons/National Archives Illegal dump along New Jersey Turnpike in photo taken circa 1970s. Image: Wikimedia Commons/National Archives

--1960s and 1970s

New Jersey's new awareness of environmental issues can be traced to the 1960s, when the impact of environmental pollution on public health and natural resources emerged as a priority political concern. In part, the new attention was provoked by a national movement which evolved following the publication in 1962 of Silent Spring, the book authored by Rachel Carson documenting detrimental environmental effects from the use of pesticides, particularly on birds. In New Jersey, the state faced a legacy of garbage dumps, toxic waste and polluted waterways as the public gained new understanding of links between environmental quality and human health. The poor quality of New Jersey's environment also contributed to the negative perception of the state's overall image. Smell from refineries which greeted motorists along the New Jersey Turnpike, along with highly visible garbage dumps, became frequent fodder for comedians. Responding to growing public pressure, the administration of Governor William Cahill enacted legislation to create the state Department of Environmental Protection effective on April 22, 1970--the nation's first official Earth day--as a separate executive department, largely consolidating existing programs from other agencies. New Jersey became the third state to consolidate its environmental protection and conservation programs into a single, unified agency, a pattern followed by the Congress later that year when the US Environmental Protection Agency was established in December 1970. -- 'Cancer Alley' and environmental health But despite the state and federal measures, environmental health concerns would continue to spark controversy. In 1973, a National Cancer Institute study (which was later discredited for faulty methodology), reported that New Jersey had the highest incidence of cancer in the nation, with 19 of the state’s 21 counties ranking in the top ten percent of all counties in the nation in cancer death rates. The report led the media to label the New Jersey Turnpike corridor, along which the highest incidence of cancer cases was identified, being labeled "Cancer Alley," with one high-level state environmental official attributing the cause to the concentration of nearby chemical plants. Renewed concerns over environmental health impacts also arose later on the local level over specific sites, such as the pollution of the Raritan River by the Kin-Buc landfill in Edison in Middlesex County and the contamination of drinking water in wells in Toms River in Ocean County by discharges from the dye and chemical plant operated by the Ciba-Geigy Corp. The identification of asbestos as a carcinogen, with one of the world's largest producers, the Johns-Manville Corporation, based in Manville, also emerged as a major national and state issue. Concerns over asbestos exposure led to the closing of schools, which was followed by a statewide program for its removal from buildings and homes, along with protracted litigation seeking damages for its effects on health of workers and others.

|

|

In the 1970s and 1980s, a series of new laws were enacted to require companies to publish inventories of toxic chemicals stored at their facilities and to track the shipping of toxic substances; set standards on the discharge of carcinogenic chemicals into the atmosphere; strengthen penalties for illegal dumping; prohibit sewage discharges into the ocean; regulate development affecting freshwater wetlands; and give citizens the right to sue to enforce compliance with environmental laws and regulations. The state also established a compensation and cleanup fund for damages from oil and toxic chemical spills, financed by a tax on the transfer of petroleum and chemicals within the state, which became the model for the federal Superfund program to remediate toxic spills and sites throughout the country. It also expanded its acquisition of open space for parks, recreation and farmland preservation through the Green Acres program, as well as imposing strict regulatory controls over development of such environmentally sensitive areas like the Pinelands and water resources in the Highlands.

According to a federal Environmental Protection Agency report released in March 2019 assessing pollution in 2017, New Jersey factories and refineries released almost 6 million pounds of toxic chemicals into the air and water during the year. The levels continue a decline in the quantity of chemicals emitted statewide from a high of 20 million pounds in 2005 to the 5.8 million in 2017. The top producer of waste was the Phillips 66 Bayway Refinery in Linden, which generated nearly half of New Jersey's total releases, comprising 33 chemicals totaling 2.7 million pounds into the air and water,

|

|

-- Current Priorities and public opinion

Current environmental priorities include the continuing federal and state efforts to clean up existing Superfund and other toxic waste sites; restrict ozone pollution within the state and from out-of-state sources to address global warming; identify expanded capacity for solid waste landfills and reduce waste generation; protect against toxic pollution from storm surges; and conserve open space areas. A state-by-state public opinion survey published in October 2020 by the nonprofit Resources for the Future found that 83% of New Jerseyans believed global warming has been happening; 86% believed past warming has been caused by humans; and 89% believed warming will be a serious problem for the United States. In a survey published in April 2019 by the Eagleton Institute of Politics at Rutgers and the New Jersey Climate Change Alliance, it was reported that two-thirds of New Jerseyans were either “very” (37%) or “somewhat” (30%) concerned about the effects of climate change on their life, their family members, or the people around them, with 15% “not very” concerned, and 18% “not concerned at all.” The survey also reported that women (73%), non-white residents (73%), and those with higher levels of education (75%) are all more likely than their counterparts to be concerned about the impact of climate change. * New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection

* EPA in New Jersey, US Environmental Protection Agency * American Lung Association in New Jersey

* Climate Insights 2020: Opinion in the States, October 2020, Resources for the Future * Climate Change Attitudes i n New Jersey, April 2019, Eagleton Center for Public Interest Polling/RutgersEagleton Poll and New Jersey Climate Change Alliance |