History- British Colonial Period

|

* Home

* History * Population * Government * Politics * Lobbyists * Taxes * State Symbols * Biographies * Economy * Employers * Real Estate * Education * Recreation * Restaurants * Hotels * Health * Environment * Stadiums/Teams * Theaters * Historic Villages * Historic homes * Battlefields/Military * Lighthouses * Art Museums * History Museums * Wildlife * Climate * Zoos/Aquariums * Beaches * National Parks * State Parks * Amusement Parks * Waterparks * Swimming holes * Arboretums More... * Gallery of images and videos * Fast Facts on key topics * Timeline of dates and events * Anthology of quotes, comments and jokes * Links to other resources |

* Native Americans * Exploration and Settlement * British colony * Royal governance * Path to Revolution * Revolutionary War * Industrialization * Civil War * Post-War Economy & Reform * Woodrow Wilson as Governor * World War I & 1920s * Great Depression * World War II * Post-War Development * 1960s & Richard Hughes * 1970s & Income tax * 1990s-Whitman & Florio * 9/11 & McGreevey Administration * Codey & Corzine * Chris Christie * Phil Murphy After the Dutch surrendered Nieuw Netherland to the English in 1664, the name of the Dutch settlement of Nieuw Amsterdam was changed to New York to honor the Duke of York. The English also promptly took command of the villages across the Hudson River. After a brief artillery display, the Swedish settlements along the Delaware River also conceded to the English claims.  Lord John Berkeley. Image: Wikimedia Commons/National Portrait Gallery, London Lord John Berkeley. Image: Wikimedia Commons/National Portrait Gallery, London

-- Proprietary Government and the Nicolls Grants

Following the assumption of English control, Richard Nicolls--now established as Governor--administered the new colony from New York and granted land rights to two groups. The first grant was composed of land between the Raritan and Passaic Rivers making up what is now Essex County; the second grant extended from Sandy Hook to Barnegat Bay and 25 miles up the Raritan River, comprising much of what is now the Jersey Shore counties of Monmouth and Ocean. The "Nicolls Grants"--which were later repudiated by the Duke of York as granted by Nicolls without authority--would continue to cloud the title to land in the colony well into the following century. Many of the first settlers pursuant to these grants were Quaker and Baptist refugees from England, some of whom had first settled in New England, but were frustrated with the difficult winters and poor soil in the north. At the direction of Nicolls, the grantees also negotiated agreements with the Lenni Lenape confirming the sale of land rights to the settlers. Meanwhile, without advising Nicolls, the Duke of York had granted 7,500 square miles or 4.8 million acres from the Upper Delaware to the Hudson to Lord John Berkeley and Sir George Carteret, two close friends who had led military forces in support of the Crown during the English Civil War and Reformation from 1642 to 1658. Without knowledge of the grant to Berkeley and Carteret, Nicolls as governor had begun to make his own grants of land to settlers, thus creating confusion over land titles in New Jersey which would later lead to conflicts and occasional violence.  Sir George Carteret. Image: Wikimedia Commons Sir George Carteret. Image: Wikimedia Commons

Dismayed at the Duke’s action, Nicolls resigned as Governor and Berkeley and Carteret assumed control by sending 26-year-old Philip Carteret, a distant cousin of George Carteret, as the new governor of what was now renamed New Jersey in honor of the Isle of Jersey, George Carteret’s native home where he had provided refuge to the Royal family during the Civil War.

Philip Carteret shown landing in 1665 in New Jersey. Image: New Jersey Historical Society Philip Carteret shown landing in 1665 in New Jersey. Image: New Jersey Historical Society

-- Governor Philip Carteret

Berkeley and Carteret set out to realize profit from their new holdings by attracting settlers through incentives such as offering liberal guarantees of religious freedom, as well as exemption from taxation not imposed by the authority and consent of the general assembly of the province. When Philip Carteret arrived in New Jersey in 1665, he found that many of the settlers under his purported control were Quakers, Baptists and other descendants of those who had fled England to escape persecution for refusing to worship in the Anglican church. The settlers also resisted the concept that they should pay “quitrents”--a feudal heritage where landowners paid sums to the local nobleman to substitute for other services the nobleman could demand--to those who had gained their property rights by patronage from the Crown. Carteret negotiated agreements with those who had purchased tracts from Nicolls, confirming their land rights in return for oaths of loyalty to the Berkeley and Carteret proprietors. In 1668, however, when Carteret attempted to convene an assembly and also sought to collect quitrent payments, he faced resistance from the purchasers of the Monmouth tract that ultimately led to the outbreak of violence in 1670. The conflict grew worse through the meddling of James Carteret, the son of Sir George Carteret, who appeared in the colony in 1672 and successfully appealed to the settlers opposing Philip Carteret to convene an assembly at which he was elected “president” of the province.

In view of the divisions within the colony over its governance, Philip Carteret sailed to England to ask the proprietors to reconfirm his authority. Ultimately, he obtained backing from the Duke of York, including decrees that the grants of land titles from Nicolls were null and void; that anyone without a title from the proprietors forfeited his land; and that refusal to pay quitrents subjected the violator to execution of the debt through forfeiture of furniture, cattle and other movable goods. The decree also strengthened the governor’s powers through declaring that only freemen could vote; that only the governor and his council could designate who was a freeman; and that only the governor could charter towns, appoint officials, establish courts or sell land that had not been previously sold. James Carteret was banished from New Jersey and departed for the Carolina colony. When he returned from England, Philip Carteret confronted an increasingly hostile colony.

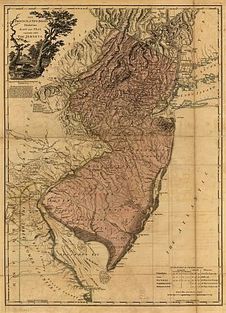

"The Province of New Jersey, divided into East and West, commonly called the Jerseys," map based on 1769 survey published 1777 by William Faden. Image: Library of Congress "The Province of New Jersey, divided into East and West, commonly called the Jerseys," map based on 1769 survey published 1777 by William Faden. Image: Library of Congress

-- Division into East and West Jersey

The colony's governance became more complicated in 1676 when New Jersey was fragmented through the sale by Lord Berkeley of his half of the colony to two Quakers, Major John Fenwick and Edward Byllynge. Soon after the sale, the purchasers from Berkeley and Sir George Carteret decided that it would be best to partition their ownership, signing the “Quintipartite Deed” splitting the province into West Jersey and East Jersey, with the Quakers assuming control of the western lands which started west of a line commencing just north of what is Atlantic City to a line on the Upper Delaware ending near the current boundary between Sussex and Warren counties. Philip Carteret’s smaller role as the governor of East Jersey was further undermined by continuing conflicts with the settlers and interference from Governor Peter Andros of New York, who asserted that the right to govern New Jersey still resided in the governor of New York. Carteret denounced Andros’s claim, but was seized by a detachment of 80 soldiers dispatched by Andros from New York to Elizabethtown. A jury convened to hear the charge by Andros that Carteret was governing New Jersey without legal authority, however, acquitted Carteret, and a similar ruling against Andros was later handed down by an arbitrator appointed by the Duke of York -- Quaker control Following the death of Philip Carteret in 1680, twelve of the wealthiest Quakers who had purchased West Jersey also bought East Jersey from Carteret’s widow with the original goal of restricting it to Quaker settlers. The Quakers soon recognized, however, that East Jersey already had too many non-Quaker residents to allow a purely Quaker community; consequently, they decided to exploit the property through real estate sales by selling off half of their interests, in “twenty-fourths,” to 12 other, primarily Scottish, speculators. The new ownership group organized themselves into the East Jersey Board of Proprietors, also seeking to sell land to new settlers. The Board of Proprietors also attempted to collect rents from the holders of the Nicolls land titles, provoking long-standing legal battles over the validity of the Duke of York’s purported nullification of the property rights granted by Nicolls. The holders of the titles from Nicolls contended that, even if the Duke of York had the power to void the Nicolls conveyances, they still held ownership through their purchases from the Lenni Lenapes, the true original owners of the land.  Sir Edmund Andros. Image: Wikimedia Commons/Rhode Island State House Sir Edmund Andros. Image: Wikimedia Commons/Rhode Island State House

In West Jersey, Quaker dominance soon was undermined by continuing land sales to non-Quakers, capped by the purchase of one million acres of land by the West Jersey Society, a consortium of London merchants. Quaker influence in West Jersey continued, however, particularly with its more democratic principles of government and human rights, such as allowing votes to all adult males, protections against arbitrary penalties or punishment and opposition to slavery.

In 1685, the Duke of York assumed the throne as King James II. His coronation also saw a renewal of the power of Sir Edmund Andros, who had solidified his relationship with the new monarch and arrived in New York in 1688 to announce that the King had designated him to head the “Dominion of New England” which would include New York and New Jersey and have Boston as its capital. In the next year, however, James II was deposed after the invasion of England by William of Orange, who was invited by the Anglican aristocracy to restore England to Protestant control from the Catholic James II.  Print depicting arrest in 1689 of Governor Andros in Boston published 1876 in "Pioneers in the Settlement of America." Image: Wikimedia Commons Print depicting arrest in 1689 of Governor Andros in Boston published 1876 in "Pioneers in the Settlement of America." Image: Wikimedia Commons

-- Resistance to Proprietary rule

The end of the brief reign of James II also closed the Andros effort to assert control of New Jersey under the Dominion of New England, but internal conflicts continued in both East and West Jersey between the landowners and their settlers. In East Jersey, the proprietors tried to maintain control by denying the vote to those who did not hold titles purchased from them, but individual towns largely ignored the edict. The Dominion of New England collapsed in 1689 when a revolt by Massachusetts colonists arrested and jailed Andros in Boston, and when news reached the other colonies they each reasserted their local control under their original charters. In 1699, an assembly controlled by those opposed to the proprietors gave the vote to all “freeholders”--all those who owned property regardless of whether the title originated with the proprietors. Violence eventually erupted against the proprietor-controlled courts with mobs invading courtrooms and freeing prisoners in Newark and Elizabethtown. In 1701, during a trial convened in Middletown by Governor Andrew Hamilton of Moses Butterworth, an alleged pirate under the command of Captain William Kidd, a mob invaded the courtroom and briefly jailed the Governor, his judges and sheriff. In West Jersey, violence also broke out in Burlington after the proprietors tried to levy a tax to pay the costs of defending their property claims. -- End of Proprietary rule

The unrest led the proprietors to seek ways to give up their claims to govern the settlers in return for confirmation of their property rights. Lewis Morris, a young landowner who had been an early critic of the proprietors, but later was selected to represent them in negotiations with the government in England, brokered an agreement in 1702 by which the proprietors' East Jersey land claims were reaffirmed, including their rights to quitrents; exemption of their lands from taxation by the assembly; exclusive authority to buy additional Indian lands; and control of the courts. Voting was restricted to those owners of 100 or more acres of property, with membership in the assembly limited to those with 1,000 or more acres. The major issue Morris failed to secure for the proprietors was their right to nominate the governor, which now became the prerogative of the Crown.

The religious and ethnic diversity that had taken root in New Jersey also generated a long-standing tradition of strong local self-government which has had lasting influence. New Jersey settlers had become suspicious of the government imposed by central authority through the proprietors, and resented the early attempts to impose religious and national controls over an increasingly diverse population. Town meetings, at which all adult males could participate regardless of the status as property owners, became key forums for debate. Since towns disposed of surplus lands at these meetings, strong economic interests also guaranteed broad participation.

Next -- Royal Governance * Native Americans * Exploration and Settlement * British colony

* Royal governance * Path to Revolution * Revolutionary War * Industrialization * Civil War * Post-War Economy & Reform * Woodrow Wilson as Governor * World War I & 1920s * Great Depression * World War II * Post-War Development * 1960s & Richard Hughes * 1970s & Income tax * 1990s-Whitman & Florio * 9/11 & McGreevey Administration * Codey & Corzine * Chris Christie * Phil Murphy |