History-- 19th Century Industrial Development

|

|

|

* Home

* History * Population * Government * Politics * Lobbyists * Taxes * State Symbols * Biographies * Economy * Employers * Real Estate * Education * Recreation * Restaurants * Hotels * Health * Environment * Stadiums/Teams * Theaters * Historic Villages * Historic homes * Battlefields/Military * Lighthouses * Art Museums * History Museums * Wildlife * Climate * Zoos/Aquariums * Beaches * National Parks * State Parks * Amusement Parks * Waterparks * Swimming holes * Arboretums More... * Gallery of images and videos * Fast Facts on key topics * Timeline of dates and events * Anthology of quotes, comments and jokes * Links to other resources |

* Native Americans * Exploration and Settlement * British colony * Royal governance * Path to Revolution * Revolutionary War * Industrialization * Civil War * Post-War Economy & Reform * Woodrow Wilson as Governor * World War I & 1920s * Great Depression * World War II * Post-War Development * 1960s and Richard Hughes * 1970s & Income tax * 1990s-Whitman & Florio * 9/11 & McGreevey Administration * Codey & Corzine * Chris Christie * Phil Murphy In its early years as a colony and state, New Jersey slowly began to develop a more diversified economy to complement its traditional agricultural base. Some of its first commercial ventures as a colony evolved into more advanced businesses; the fur trade with the Native Americans, for example, evolved into hatting and coat factories which made the later cities of Orange and Newark leading national centers. Water power, which long had been used by farmers to serve grist mills, was now seen as a resource for industrial machinery. New Jersey iron mines provided raw materials for the emerging metal refining and fabricating industries. The increasing numbers of foreign immigrants, many lacking interests or skills in farming, served as a ready source of labor. Since much of its economy had failed to diversify beyond farming, state policy-makers encouraged new investment in development to reduce dependence on the growing cities of New York and Philadelphia for consumer goods and banking and financial needs.

Seal of the Society for Establishing Useful Manufactures. Image: PatersonGreatFalls.org Seal of the Society for Establishing Useful Manufactures. Image: PatersonGreatFalls.org

-- Paterson and the Society for Establishing Useful Manufactures

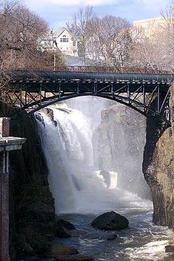

In 1791, Alexander Hamilton, secretary of the treasury in the Washington administration, submitted a report to Congress arguing that the new nation could not succeed as a purely agricultural society, and that the government should support efforts to promote manufacturing. The report also referred to a private venture backed by Hamilton to raise capital for a corporation whose purpose was to build an industrial city, with its first project the "making and printing of cotton goods." In part, Hamilton selected New Jersey as the site for the operations because, as he wrote, the state had "scarcely any external commerce," and would be unlikely to harbor interests "hostile to the advancement of manufactures." During the Revolution, Hamilton had seen the Great Falls when he picnicked above it with Washington, Madison and others during a break in the conflict.

In 1791, the venture became the first corporation chartered by the State of New Jersey, taking the name of The Society for Establishing Useful Manufactures, and was granted a “perpetual monopoly” for manufacturing in Paterson. The Society also functioned as Paterson’s only effective government until 1830 and was given tax immunity under the City’s first charter adopted in 1831. Hamilton also drew up the charter for the Associates of the Jersey Company to develop what is now the waterfront of Jersey City, again receiving generous incentives, tax exemptions and protection from competition.

The ventures promoted by Hamilton ultimately failed due to its problems in raising sufficient investment capital and mismanagement, but they did set the stage for later, more successful efforts by others to develop New Jersey as an industrial center. After struggling through recessions during the early years of the nineteenth century and the trade embargo imposed during the War of 1812, Paterson's early struggles eventually led to a growing number of successful enterprises, with new factories producing heavy machinery, other metal products and textiles.  "The General," one of the best-known locomotives produced by the Rogers Locomotive Works, on display in Kennesaw, Georgia. Image: Harvey Henkelmann via Wikimedia Commons "The General," one of the best-known locomotives produced by the Rogers Locomotive Works, on display in Kennesaw, Georgia. Image: Harvey Henkelmann via Wikimedia Commons

In 1836, Samuel Colt founded the Patent Arms Manufacturing Company below the Great Falls, where he first manufactured his newly patented repeating firearm, the revolver which would become a fixture of the Western frontier. In the 1850s, the Rogers Locomotive Works of Paterson had become the nation's leading producer of locomotives, turning out over 100 each year. By 1900, Paterson became known as "Silk City," hosting 175 different silk mills employing over 20,000 workers in often harsh conditions which later would provoke violent labor strife.

-- Camden and Amboy Railroad and the Joint Companies

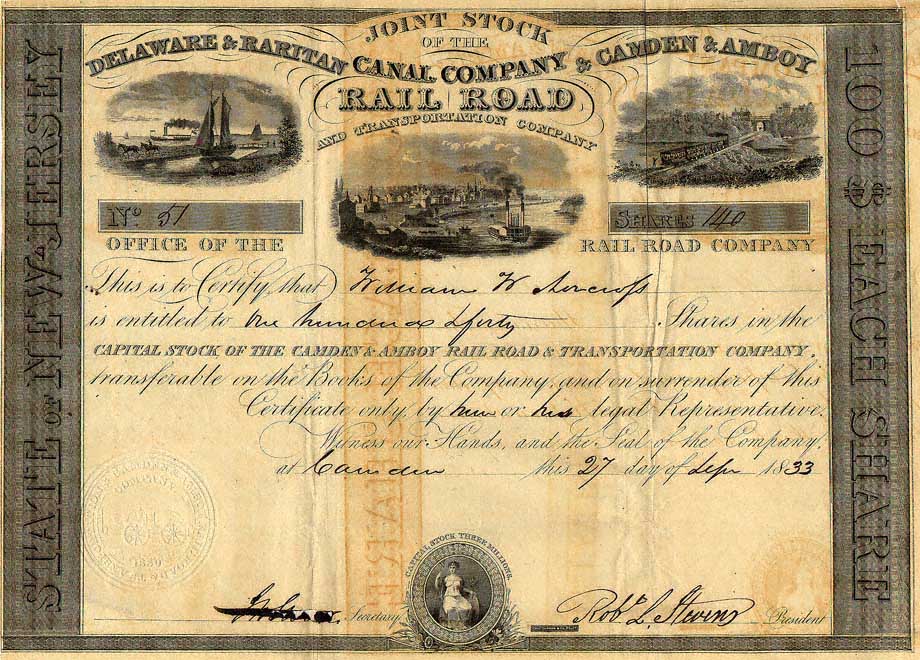

Bridges, canals and toll roads also became a new source of economic growth and government revenue, with transportation revenues financing most of the State government’s expenses. In 1830, the New Jersey Legislature granted a charter for the Camden and Amboy Railroad after first rejecting the earlier petition for a charter submitted in 1811 by the railroad’s founder, Colonel John Stevens of Hoboken. The 30-year monopoly granted the railroad exclusive rights to convey rail passengers between the Hudson and Delaware rivers in return for the State government's being given 1,000 shares of stock in the company and a guarantee of $30,000 annually from taxes imposed on rail passengers and freight. In the year after receiving its charter, the Camden and Amboy was also allowed to combine operations with the Delaware and Raritan Canal Company, founded by the Stockton family of Princeton and which initially had competed with the Railroad for investors, in an entity known as the Joint Companies, effectively giving it exclusive control over both rail and water transport in the lucrative New Jersey corridor connecting New York City and Philadelphia. The monopoly allowed the Camden and Amboy to charge what were considered at the time exorbitant rates for transporting passengers and freight through the corridor. A second-class fare between New York and Philadelphia on the Camden and Amboy was $2.50 when the average weekly wage for a worker was $1. At the same time, the railroad quickly gained a reputation for neglecting safety of its rail line and its engines and cars. Just two months after it began operation with steam locomotives in 1833, the Camden and Amboy had the first railroad accident resulting in deaths, when two were killed in its run from Hightstown to Spotswood. Among the injured was Cornelius Vanderbilt, who broke a leg and vowed never to travel by train again, ironically later becoming one of the nation's wealthiest individuals through his ownership of railroads including the New York Central. Another passenger was Congressman and former US President John Quincy Adams, who was uninjured, but wrote in his diary that the accident was "the most dreadful catastrophe that ever my eyes beheld." |

|

The revenue from the rail and canal monopoly enabled the Legislature to pass most of the costs of government to those traveling through the state, thus avoiding the political risks of imposing direct taxes or fees on New Jersey residents. At its peak, revenues to the state government accounted for about a fifth of its total budget. The economic leverage of the Joint Companies also extended to domination of New Jersey government and politics through both open and covert support of those sympathetic to its interests, primarily in the Democratic Party. The corruption which resulted led outsiders to deride New Jersey as the "State of the Camden and Amboy."

is a reference to the Camden and Amboy Railroad. The railroad was chartered by the state of New Jersey in 1830, and it was the first railroad in New Jersey and the third in the United States 12. The railroad was so influential that it gained a reputation as “the influence behind the throne, greater than the throne itself” 3. The chief strategist of the monopoly was Robert F. Stockton, who was instrumental in brokering the consolidation of the canal and railroad companies 3. He reputedly boasted that “he carried the State in his breeches pocket, and meant to keep it there” 3. Whenever the monopoly was attacked, Stockton and its other apologists invoked the sanctity of contracts, states’ rights, and the financial benefits to the state 3. Matters came to a head in 1848 when a series of letters by Henry C. Carey appeared in the Burlington Gazette. In addition to reciting the usual complaints against the monopoly, Carey accused the Joint Companies of gouging the public and concealing profits in their reports, thereby defrauding the state. The Joint Companies ultimately refused his demand to inspect their books 3 -- Banking and Finance

The chartering of banks to support the new industrial and commercial ventures also served as a means for New Jersey to avoid broad taxes. When the Newark Banking and Insurance Company was chartered in 1804 as New Jersey's first bank, the Legislature included a clause in the charter reserving a designated number of shares for the State if the Legislature exercised its option to subscribe. This practice continued with several later charters; rather than exercising its option to buy shares and participate in bank management, the Legislature generally chose to sell its rights, thus generating revenue for the State treasury. |

In 1847, William Colgate relocated his soap plant from New York to Jersey City, soon shipping its growing consumer product line to customers across the country. The Colgate complex would eventually grow to cover seven blocks with 44 buildings, in which soaps, talcums, toothpaste and other products were made. Other toiletries evolved from a pharmacy opened in 1879 by Gerhard Mennen in Newark, which later became the Mennen Company.

In Camden, what later would become the Campbell Soup Company was started in 1869 by Joseph A. Campbell, a fruit merchant and Abraham Anderson, an icebox manufacturer. Initially, they produced, in addition to soups, canned tomatoes, vegetables, jellies, condiments, and minced meats; when Anderson left the partnership in 1876, the company reorganized as the "Joseph A. Campbell Preserve Company." Some twenty years later, it grew rapidly after John Dorrance, a nephew of the plant's general manager and a chemist with degrees from MIT and Göttingen University in Germany, developed a commercially viable method for condensing soup through reducing by half the volume of water, thus saving storage and shipping costs. Dorrance went on to become president of the company from 1914 to 1930, eventually buying out the Campbell family. -- Tourism

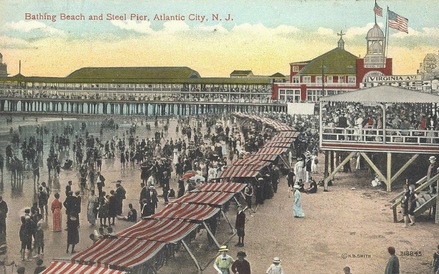

Tourism, a sector often not considered in the nineteenth century as a part of New Jersey's economy, would evolve to become one of the state's largest job producers. In the 1830s, Cape May (then known as Cape Island) became the nation's first summer resort, hosting affluent families, including many southern plantation owners escaping the heat at home. As it became increasingly popular, larger hotels were built. The New Atlantic, opened in 1842, could accommodate 300 guests. A two-week stay in 1847 by Senator Henry Clay reinforced the Cape's position as the leading seaside resort in the country. In 1852, a group of investors began construction of the largest hotel in the world, the Mt. Vernon Hotel, intended to serve 3,500 patrons, but it was still unfinished when it was consumed by fire in 1856 while it was accommodating 2,100 guests. In 1878, after another fire devastated much of the village, Cape May rebuilt, but deliberately chose to redevelop with smaller inns and boarding houses, avoiding the large hotels of competing resorts. To the north, the beaches of Absecon Island remained largely free of visitors until Dr. Jonathan Pitney, a young physician who envisaged the area as a health resort, succeeded in getting the legislature to charter a new railroad from Camden to the shore. The railroad's completion in 1854, the same year that Atlantic City was incorporated, led to explosive growth based on the new concept of short-term stays by workers and their families with limited means, a sharp distinction from the wealthy visitors spending summers at the older resorts of Cape May and Newport. By 1874, nearly 500,000 passengers a year were coming to Atlantic City by rail, attracted not only by its beaches and popular entertainment but also by its reputation for openly ignoring restrictions on drinking, gambling and prostitution. At the turn of the century, 27,000 people lived year-round in the city, a dramatic gain from the estimated 250 in 1855. In Monmouth County, after the Civil War, Long Branch hosted visits by seven presidents: Ulysses S. Grant, Chester A. Arthur, Rutherford B. Hayes, James A. Garfield, Benjamin Harrison, William McKinley, and Woodrow Wilson. After he was shot on July 2, 1881 at the rail station in Washington, President Garfield was brought to Long Branch, with his trip eased by a specially laid rail from the central rail station to the beachfront home of his convalescence, in the hope that the fresh sea breezes might aid his recovery, but he died here on September 19, 1881. Other shore towns began as religious retreats, particularly those established by the Methodist Church where preachers would deliver sermons to congregations who would stay in tents on or near the beach. Gradually, the tents would be replaced by more permanent structures and homes. The Ocean Grove Camp Meeting Association was organized in 1869 by a group of thirteen ministers and thirteen citizens, and sponsored the first camp gathering during the summer of 1870. In five years, there were 600 tents, 400 cottages, and seventy-nine hotels and boardinghouses. Its popularity later attracted some of the nation's most prominent preachers such as Billy Sunday. Unlike wide-open resorts like Atlantic City, dancing, card-playing, alcohol, tobacco, and driving on Sundays were forbidden. In 1894, its Great Auditorium was completed, with seating for 10,000, and offering programs of sermons, religious music and family entertainment.. Other shore towns began as religious retreats, particularly those established by the Methodist Church where preachers would deliver sermons to congregations who would stay in tents on or near the beach. Gradually, the tents would be replaced by more permanent structures and homes. The Ocean Grove Camp Meeting Association was organized in 1869 by a group of thirteen ministers and thirteen citizens, and sponsored the first camp gathering during the summer of 1870. In five years, there were 600 tents, 400 cottages, and seventy-nine hotels and boardinghouses. Its popularity later attracted some of the nation's most prominent preachers such as Billy Sunday. Unlike the wide-open resorts like Atlantic City, dancing, card-playing, alcohol, tobacco, and driving on Sundays were forbidden.

-- Movement for reform Toward the end of the century, New Jersey's long-standing policy to seek revenue from business enterprises to avoid general taxes arose in a new context as the state passed laws designed to attract corporations to establish their legal headquarters in the state, taking advantage of New Jersey's lax controls on anti-competitive practices and the creation of monopolies. As it was derided earlier in the century as the "State of the Camden and Amboy," muckrakers such as Lincoln Steffens now branded New Jersey as the "traitor state." In 1905, Steffens bluntly charged: "New Jersey sold us out for money. She passed her miscellaneous incorporation acts for revenue. And she gets the revenue. Her citizens pay no direct state tax. The corporations pay all the expenses of the state, and more." Next --Civil War |

* Native Americans * Exploration and Settlement * British colony * Royal governance

* Path to Revolution * Revolutionary War * Industrialization * Civil War

* Post-War Economy & Reform * Woodrow Wilson as Governor * World War I & 1920s

* Great Depression * World War II * Post-War Development * 1960s & Richard Hughes

* 1970s & Income tax * 1990s-Whitman & Florio * 9/11 & McGreevey Administration

* Codey & Corzine * Chris Christie

* Phil Murphy

|

|