* Home

* History

* Population

* Government

* Politics

* Lobbyists

* Taxes

* Biographies

* Economy

* Employers

* Real Estate

* Law Firms

* Venture Capital

* Growth Companies

* Labor Unions

* Education

* Recreation

* Restaurants

* Hotels

* Health

* Environment

* Stadiums/Teams

* Theaters

* Historic Villages

* Historic homes

* Battlefields/Military

* Lighthouses

* Art Museums

* History Museums

* Wildlife

* Zoos/Aquariums

* Climate

More...

* Gallery of images and videos

* Fast Facts on key topics

* Timeline of dates and events

* Anthology of quotes, comments and jokes

* Links to other resources

|

|

-- Environment - Solid & Hazardous Waste

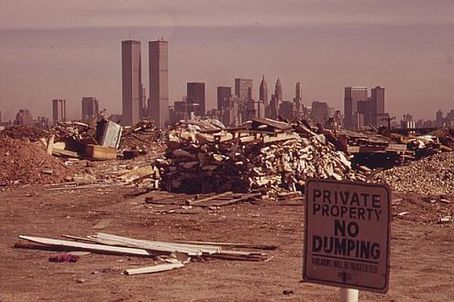

Dumping in Jersey City north of current Liberty State Park just off New Jersey Turnpike in photo taken in 1973. Image: US Environmental Protection Agency/National Archives Dumping in Jersey City north of current Liberty State Park just off New Jersey Turnpike in photo taken in 1973. Image: US Environmental Protection Agency/National Archives

-- Overview According to the state Department of Environmental Protection, in 2010, the most recent year of published data, New Jersey generated 22 million tons of solid waste, about 5,000 pounds per person, and recycled 13.3 million tons, 60.5% of the total amount generated. Of the 8.7 million tons which were not recycled, 38% was deposited in landfills within the state; 37% shipped to landfills outside the state; and 25% incinerated within the state. The DEP listed 13 operating commercial public landfills in 2015, but also identified a total of 854 active, closed and possible illegal public and private landfills and other waste disposal sites in the state. As of 2011, there were approximately 1,300 licensed haulers of solid waste in the state. The most recent state Solid Waste Management Plan was published in 2006, and called generally for efforts to increase recycling and reduce waste generation. Nationally, the US Environmental Protection Agency reported that in 2013, about 254 million tons of trash was generated. with recycling and composting accounting for about 87 million tons of this material, equivalent to a 34.3% recycling rate. On average in all states, recycling and composting represented 1.51 pounds of individual waste generation of 4.4 pounds per person per day. * Bureau of Solid Waste Compliance and Enforcement, New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection * Solid Waste and Recycling, Division of Solid and Hazardous Waste, New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection * New Jersey Landfill List, New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection * Statewide Solid Waste Management Plan 2006, Division of Solid and Hazardous Waste, New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection * Materials and Waste Management in the United States: Key Facts and Figures, US Environmental Protection Agency -- Laws and regulation The regulatory authority over the collection and disposal of solid waste in New Jersey is derived from two separate laws enacted in 1970: the Solid Waste Management Act (N.J.S.A. 13:1E-1 et seq.), which empowers the DEP to license and set environmental standards for shippers, landfills and others, and the Solid Waste Utility Control Act, (N.J.S.A. 48:13A-1 et seq.), which authorizes the Board of Public Utilities to regulate rates set by those in the industry and to prohibit practices such as favoritism, corruption and bid-rigging, The federal Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA) enacted in 1976 authorizes the US EPA to set minimum national technical standards for how disposal facilities should be designed and operated, with states delegated the power to issue permits to ensure compliance with regulations for the disposal of solid and hazardous waste. * Overview of Solid Waste Control Laws, New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection * Resource Conservation and Recovery Act After the enactment of the legislation in 1970 giving the state government the principal oversight role in solid waste disposal, other New Jersey attempts to conserve space for its own waste through restricting access by out-of-state sources to in-state landfills and to control the flow of waste disposal within or near New Jersey have faced legal obstacles. In Philadelphia v. New Jersey, 437 U.S. 617 (1978) the United States Supreme Court barred New Jersey from restricting the ability of private landfill operators to accept and process solid waste from outside the state on the ground that the prohibition violated the commerce clause of the US Constitution. In 1995, another federal court decision invalidated the state's effort to mandate that waste within counties be disposed of at central incinerators or other disposal facilities designated by each county government, a decision again based on the federal Constitution's commerce clause. See Atlantic Coast Demolition and Recycling, Inc. v. Board of Chosen Freeholders of Atlantic County * Philadelphia v. New Jersey, 437 U.S. 617 (1978) * Atlantic Coast Demolition and Recycling, Inc. v. Board of Chosen Freeholders of Atlantic County, 48 F.3d 701 (3d Cir. 1995) In addition to land disposal issues, the use of the Atlantic Ocean for the dumping of garbage and sewage sludge, which resulted in periodic episodes of the fouling of New Jersey beaches, also has been addressed through both judicial and legislative actions. An estimated 25 million tons of waste including scrap metal, chemicals, and acids were dumped into the ocean. As early as 1929, New Jersey sued New York City to stop its dumping of waste off the New Jersey coast, a case ultimately decided on appeal by the US Supreme Court, which barred the disposal of municipal waste collected from residential buildings, but not commercial or industrial waste. See New Jersey v. New York City, 290 U.S. 237 (1933). It was not until the federal Ocean Dumping Act was enacted in 1972 that a limited ban was first imposed on ocean dumping, but more comprehensive prohibitions effective in 1977 and 1988 further restricted disposal of sewage sludge and industrial waste. In the summers of 1987 and 1988, the so-called "Syringe Tide" of medical waste forced the closure of several New Jersey beaches, resulting in an estimated $1 billion in losses to the state's economy and leading to the enactment of the federal Medical Waste Tracking Act to require health care providers and others to document each step in waste disposal. The last permit for dumping of construction debris was issued in 1988 and sewage sludge disposal was halted in 1992. Ocean dumping is still allowed for some materials, however, such as dredged materials and fish waste. The state's beaches also continue to experience periodic closures due to illegal dumping or stormwater sewer overflows. * New Jersey v. New York City, 290 U.S. 237 (1933) * Ocean Dumping Act of 1972 * Medical Waste Tracking Act of 1988 * Managing Ocean Dumping in EPA Region 2, US Environmental Protection Agency  Superfund site in Edgewater. Image: US Environmental Protection Agency Superfund site in Edgewater. Image: US Environmental Protection Agency

-- Hazardous waste Hazardous waste has been of special concern in New Jersey due to its association with adverse health impacts and the legacy of decades of unregulated disposal of chemicals and other toxic materials. The state's industrial corridor along the Passaic River and roughly tracking the cross-sate route of the New Jersey Turnpike was labeled following a 1976 study as "Cancer Alley" for the high cancer rates reported in the region (although the findings later were largely discredited.). Residential, industrial and commercial waste deposited in landfills and other disposal sites contains a variety of metals and chemicals, including lead, mercury, asbestos, dioxin and polychlorinated biphenyls that have been found to pollute rivers and groundwaters as they leach through surface soils. The Spill Compensation and Control Act was enacted in 1976 and became the model for the federal Superfund Act (Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act of 1980 or CERCLA), which broadly authorizes the US EPA to clean up contaminated sites and releases or threatened releases of hazardous substances that may endanger public health or the environment Subsequent .state legislation established chemical monitoring and disclosure requirements for chemical use in the workplace and for tracking their shipping and disposal which gave New Jersey perhaps the most stringent legal controls over chemicals of any state. As of 2015, there were 1,322 Superfund sites on the National Priorities List in the US, with New Jersey having the largest number of all states with 115 sites. Sites identified as having the most severe pollution include the former E.I. DuPont Co. explosives plant in Pompton Lakes and the former Diamond Alkali plant in Newark which produced the Agent Orange chemical defoliant, resulting in extensive dioxin pollution of the Passaic River. * Materials and Waste Management in the United States: Key Facts and Figures, US Environmental Protection Agency * CERCLA Overview, US Environmental Protection Agency * New Jersey Landfill List, New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection * Superfund Sites in US, US Environmental Protection Agency |